Top fashion firms pledging to end worker exploitation in their supply chains are hampering progress through irresponsible sourcing practices, according to a report by the Universities of Sheffield and Bath and Royal Holloway under the University of London. It found major brands impose short production windows, cost pressures and constant order fluctuations. These make it difficult for local suppliers to comply with the standards of working conditions that companies including Nike, H&M, Adidas, Primark and Walmart expect.

The report, ‘Decent Work and Economic Growth in the Southern Indian Garment Industry,’ is part of the British Academy’s international programme, Tackling Slavery, Human Trafficking and Child Labour in Modern Business, funded by the British Academy in partnership with the UK Department for International Development.

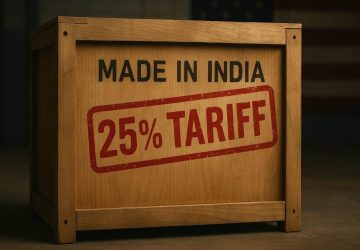

The report focused on the garment industry clustered around Tiruppur in Tamil Nadu State, which accounts for 45-50 per cent (around $3.6 bn in 2017) of all knitwear exports from India. Suppliers in the region have improved their working conditions over the past decade. However, heightened competition from lower-cost countries like Bangladesh and Ethiopia has meant that brands can force prices down, leaving little scope for further ethical improvements, statements from the universities said citing the report.

The research found that social audits, intended to call out exploitation, are frequently manipulated and cheated by suppliers to retain business with brands. Suppliers complain that such ethical certification systems are too costly and add little value.

Interviews with more than 135 business leaders, workers, NGOs, unions and government agencies in the State of Tamil Nadu during 2018 uncovered considerable evidence that while top-down initiatives from brands have led to some improvements in working conditions, they have failed to eradicate labour exploitation.

Professor Genevieve LeBaron, co-author of the report and Professor of Politics at the University of Sheffield, said: “Workers told us about extensive and shocking violations of their rights, including routine disregard for health and safety standards, restricted freedom of movement and verbal abuse. They also reported incidents of child and bonded labour, and told us how they suffered from gender discrimination, unfair pay, a lack of contracts, and limited freedom to speak, among other violations of their rights.”

“Brands can’t have it both ways. They are demanding ethical labour practices and living wages from suppliers, but they aren’t paying enough or changing their business models to make these possible. It’s crucial that these companies recognise the impact of their requests for cheap, fast fashion on the people who make their clothes,” LeBaron said.

Andrew Crane, co-author and professor of business and society at the University of Bath’s School of Management, said: “When we interviewed manufacturers who supply knitwear to major global brands they explained that brands are growing louder in their demands for an end to bad labour practices but they are unwilling to alter their commercial practices to support improvements.”

“Brands need to ensure that local businesses are supported in their efforts to pursue decent work, and are not, as is all too often the case, squeezed by buyer demands that push them towards more exploitative practices,” he said.

The researchers are calling for the formation of a new taskforce in Tiruppur to solve the labour issues facing the industry, led by an independent organisation or chair. They highlight three key issues to achieve decent work and economic growth: Freedom of movement, health and safety, and worker-driven social responsibility – and have made 12 recommendations to achieve this.